Preparing for battle in Tales of Vesperia turns you into a pencil pushing, Excel spreadsheet clicking, managerial maniac. Actual battle is a complete chaotic mess. And that’s okay. Honestly, it’s pretty fun.

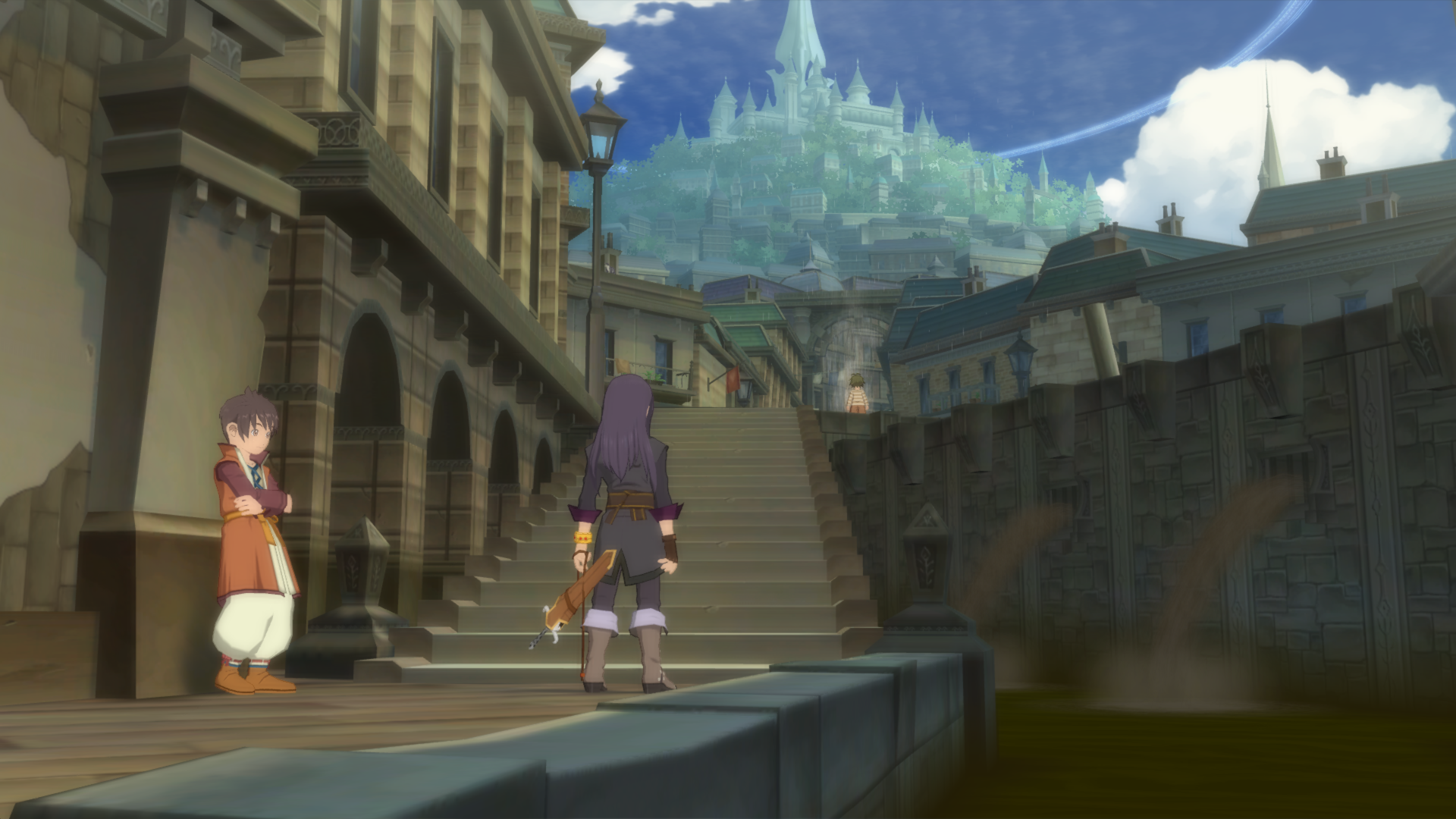

One of the first things you’ll notice in Tales of Vesperia when walking down the steps of the inn during the first minute of the game is the fixed camera perspective.

For a few (in 2008!), it might have been kind of a turn off. But I’m willing to bet that most people were at least a little stunned by what awaited them at the bottom of the steps in front of that inn.

It’s this amazing shot of our character standing closely in front of the camera, with the inn in view and a sewer reservoir filled with dirty water off to the right. There’s a set of stairs leading up to a higher platform, in an area called the lower quarter, which is a living district for the working class in the capital city Zaphias.

Those stairs lead our eyes upwards to a breathtaking view of the royal quarter, an area reserved for the upper-class nobles of the empire. It stands brightly despite the clear blue-sky backdrop.

It’s the first ‘curated’ shot of the game, and it’s a really good one. There’s this immediate juxtaposition between the nasty ass water coming off the stained bricks of the sewer system and the strangely soft, angelic cityscape high up in the distance.

It’s like a place we’ll never reach. Some far-off goal. It helps that our player character, Yuri, seems to be looking at the same sight that we have our eyes on. Somehow, we get the feeling it’s clearly not the first time for him, he’s likely had the same view of the capital for years.

You could go on and on analyzing this one fixed camera perspective (a picture is worth a thousand words, and all that). And there’s a lot more like it.

But it also brought to my attention how useful fixed cameras can be in games. Of course, there’s a lot of downsides to it that we’re all aware of. For example, one of the most basic human functions is taken away from us: we can’t look. At least, not always where we want to.

Despite those downsides, there are also a lot of hidden benefits to it as well. One of them being, of course, the ability to set up wonderful visuals without the need for the biggest, baddest, cutting edge graphics that money can buy.

The camera techniques used in Tales of Vesperia work really well. It borderline even follows photography rules like the rule of thirds. Many of the shots are visually stimulating, and a lot of that comes down to the composition.

It’s also good for pointing the player towards interesting things.

Occasionally, the camera will fixate on a particular spot in a room, or a segment of the environment outdoors. In those instances, there’s probably something you can collect or a key mechanic that you need to interact with.

There’s a weird moment of curiosity when the camera zooms in slowly on a fountain or door. We end up wondering what useful item is inside or what weird thing is going to happen there.

In a way, the designers can skip a lot of the work that goes into creating a level that flows well. Take a lot of modern, linear Triple-A games. The level designers use a lot of techniques to nudge players towards progress, without loudly yelling at them with blinking arrows of the way forward.

They’re usually really subtle tweaks to the environment, that aren’t exactly anything to give more than a second thought to on their own. Like a flashing lightbulb illuminating a doorway or paint streaked in a certain direction. But they affect players on a subconscious level and steer them towards progress.

That one facet of level design is honestly an art in itself. But you don’t need to do all that work when you can just point people where you want them to go with a camera!

But, besides progression, there are other, more interesting ways perspectives are used in Tales of Vesperia.

For example, during a segment with invisible ghost monsters, the player will find themselves in hallways filled with mirrors. In those hallways, the perspective takes a more 2D approach as the player ‘side scrolls’ across the screen.

While that’s visually interesting, it also gives you a perfect view of what the mirrors are showing. And those invisible monsters, in a vampire-esque moment of exposure, can be seen in them.

During these moments, the player has to be careful not to allow those monsters to sneak up behind them and trigger a ‘surprise attack’, whereby the player is at a disadvantage (albeit not a very large one). And they do that by looking in those mirrors, that are so conveniently displayed with the help of the fixed camera perspective.

To be fair, its possible to house these same mechanics with a controllable camera. However, it’s easier for the designers to get us to engage with mechanics by pointing us in the right direction.

There’s a ton of ‘set pieces’ like this in the game. While not all of them are that interesting, the cool that the designers take full advantage of the fixed camera perspective and turn it into a really useful and fun storytelling tool.

Plus, it’s nice not having to do the extra work moving the right analog stick. I like being lazy. It’s fun.

You can’t be lazy in other aspects of the game. Particularly with the combat.

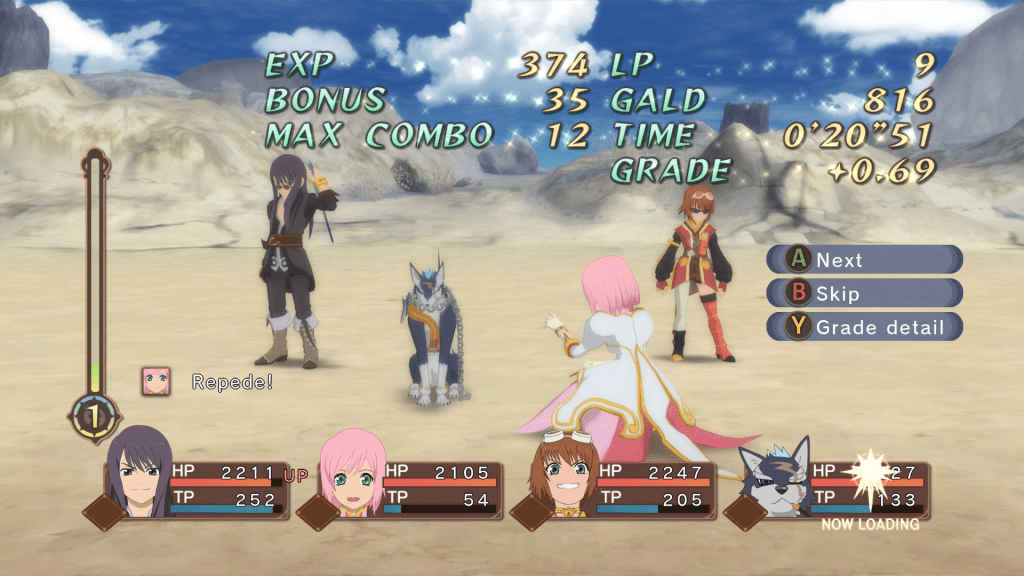

In traditional JRPG fashion, you can set your party members to ‘auto’; they make their own decisions about what to do during combat. Well, it’s not that you can set characters to auto. You actually have to.

You see, Tales of Vesperia’s combat is real-time. Anything and everything that can happen during a battle is happening all at once. Fireball spells get sent flying across the screen. One party member is duking it out with a scorpion in the corner. Another is yelling at you to toss them a consumable item. A monster is rampaging in the middle of the arena.

It’s chaos, and the game does it really well. It’s honestly fun to be in the middle of that trying to figure out what to do at any given moment.

You need to change tactics on the fly, and tell your group to rush in or be conservative, among a sizeable list of commands you can give. Of course, they might not follow your instructions to a tee, so you need to be there for support.

There’s this whole game-within-a-game going on where during one instance, you might want to focus on defending your healer, Estelle, from an aggressive set of assassin enemies. In another, it’s probably best to just run in there and kill everything as fast as possible alongside offensive party members like Judith or your dog, Repede (interestingly pronounced Rapido).

Initially, moments where you’re wondering if you should allow a character use an item weigh heavy on the mind. Later on, you end up just throwing caution to the wind and letting them do whatever they want.

There’s actually an option in the game that lets characters use consumables automatically, with a button for canceling that action, in addition to the button for allowing it. I’m pretty sure it’s the default setting now that I think about it. However, I turned it off because the thought of giving A.I. characters that much free will terrified me!

Now, during end game moments, I realize that it’s actually better to let them do their thing, with the option to cancel their item usage being left up in the air. Those couple of seconds where your brain registers that a party member is requesting an item and you actually allowing it to happen can mean life or death for that character a lot of the time.

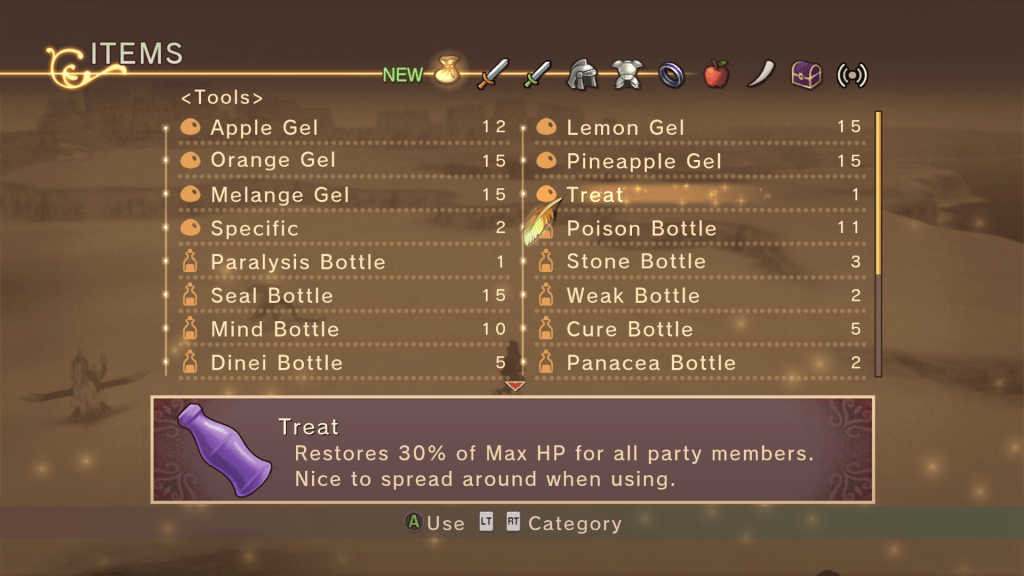

Granted, when they die another character can just revive them with a Life Bottle. Most people would be compelled to conserve those for a late game boss fight or something. But in this game, it’s perfectly normal to use a Life Bottle, even in the most mundane of trash fights. And that’s because consumable items, along with a lot of other systems in the game, don’t serve their conventional purpose.

In a lot of JRPGs, consumable items are a good way to heal, or apply a status effect, or a number of other things during combat. They’re sort of like a trump card, you use them when you’re in a pinch and don’t want to waste resource like MP to cast spells.

It’s like a reward for bringing the right tools to the job, and for saving them up for a particular point in the game. The thing is, in Tales of Vesperia, combat acts as more of a check to see if you have those items in the first place. Like it’s a prerequisite for doing well.

Here’s why: no matter what happens, eventually someone is gonna get knocked out. Especially during a boss fight. That’s just the nature of a chaotic battlefield.

In a turn-based game, in most cases, ways to circumvent this through micromanagement and careful planning. But when combat is real-time, and when your friends are A.I. controlled, you pretty just have to take your losses and move on.

But, if you come prepared, you can prevail. Accept people will get knocked on their ass, and stock up on fifteen Life Bottles.

Make sure that for every moment one of your friends cries out for a potion in the heat of battle, during a crucial turning point in a fight, that you have an answer. If you do, you win.

It’s an interesting form of party management that gets you feeling like a true leader, because the nature of items extends its slimy tendrils into other parts of the game.

For one, you need gold to be able to afford all those goodies, and the best ones aren’t cheap. Of course, you can find them occasionally in chests out in the wilderness or abandoned towns, but you definitely don’t want to bank on that when you find yourself out of Lemon Gels (an item that restores the resource needed to use spells and abilities, of which you need a lot of, trust me).

So, you end up talking with shop keepers in every city in the world stocking up on every consumable you can carry. Emphasis on carry, because there is a limit to how much of one item you can have in your inventory.

The limit is a weird psychological trick. It gets you to feel like you need to fill your stock up every time you spend time shopping for items. That effect is compounded since the limit is always ten or fifteen units. You end up thinking, “Hey, that’s not that much. Might as well go all the way!”

And it isn’t that much. Compared to the overflowing amounts of gold coming out of your bag, splurging on the bare essentials is incredibly inexpensive. It does get more costly later on, but by then the amount of gold coming into your bottom line is scaled up to match it.

Since stocking your inventory to the limit of consumables costs a relatively fixed amount, it starts to become a sunk cost. It’s just another item on the budgetary spreadsheet.

If we’re reaching, you end up managing and facilitating your party’s success through gold. By diving into the menus and figuring out what you need to survive the coming battles. By mitigating uncertainties through preparation.

Interestingly, this line of thinking can pretty much be carried over to every other system that surrounds combat in the game.

Alongside items at shop vendors is a healthy number of weapons and armor your party members equip. You can buy the standard ones for a pretty hefty price, but that’s boring. Instead, you’re encouraged to synthesize them.

When you synthesize weapons, they come with skills that the user can take advantage of. Things like increased strength, or magic attack, or more defensive qualities. There are also the more complex things, like occasionally being able to instantly cast a healing spell when attacked or adding an extra attack to a character’s combo string.

Equipping party members with those skills can be incredibly useful.

Take Auto Medicine, for example. If you find a weapon that possess this skill and equip it on Estelle, you party’s resident healer, you don’t have to worry so much about obsessively protecting her from enemies since she’ll instantly heal herself upon being attacked. That gives you more time to get over there and white knight for her.

Or FS Bonus 2, which gives the equipped character TP (skill resource) upon using the Fatal Slash technique to finish off an enemy. Put that on Yuri, the main character (and the character that most people will use when they play). If you’re having trouble with TP management, that definitely helps.

Now, you can only use those skills when you have that weapon equipped, since the skill is tied to the weapon. However, given enough time in battle, your character can learn that skill for themself!

At that point, if you take off that weapon, they can still use the skill, providing the opportunity to equip another weapon with more skills! When they learn those skills, you can take it off and put another one on. . . DO YOU SEE WHERE I’M GOING HERE?!

The weapons serve conventionally as a raw stat increase. But they also serve as a form of progression for all your party members! When they get new weapons, they also start learning new skills!

You end up spending a lot of time diving in the shop menus and looking for weapons that both have good stats, but more importantly have good and fun skills. Even if the weapon doesn’t have the best attack rating, players will still equip it on a character so they can learn its skills. Once the process is complete, they can go back to using their best sword, or wand, or whatever else they were using.

It’s a really fun form of character building because players will constantly be looking for new gear, not for stat increases, but for new skills they can learn. And the designers clearly spent the time to create a lot of skills that are genuinely interesting.

What happens is that you end up searching for skills that complement whatever ‘build’ you’ve set for your character.

If you’ve made Yuri a hyper aggressive attacker, you’re going to look for skills that complement that playstyle. Like Cross Counter, which does extra damage to enemies you catch in the middle of taking a swing at you.

Of course, you can’t just put any skill you want on your character, since it’s limited by your skill points, or SP. You end up having to carefully consider what you want to keep and what you want to unequip. Once players end up collecting tons of skills, there’s genuine conflict between what they might consider to be worth having in their arsenal.

But that makes it all the better. As Sid Meier said (and as everyone loves to quote, including me), “A game is about making interesting decisions”.

It’s hard to choose what you want to use, but ultimately, that’s what it’s about. And it becomes a really cool form of player expression.

Collecting a pile of abilities for Yuri (or however you decide to play as) is one thing. It helps accentuate whatever style of fighting you find fun to play. But it’s an entirely different ball game for the rest of your crew. Mainly. . .because you’re not playing as them.

Like the case of Auto Medicine with Estelle, learning skills is more of a way to close up any gaps and uncertainties that you might encounter in battle. It’s also a way to boost the natural strengths of each party member.

This is kind of a reach, but all of your other party members start to look more like character sheets that you fill with skills and attributes. Your hope being that whatever combination you picked increases their efficiency or helps them do their job better in some way.

If we’re talking about a healer, we hope they heal more and can defend themselves more easily. If we’re talking about a mage, we hope they have access to as much damage as possible.

We end up managing our party’s success, in this case not with gold, but with skills. We hope that with the right skills we can mitigate the uncertainties of battle. By diving into the menus and skill sheets to overcome obstacles through preparation.

When you look at all the games systems, with all the item management and skill learning and everything else, half of the combat feels like it takes place in the menus. And it’s surprisingly fun to play.

Unfortunately, the novelty of these systems wears away over the course of the game. New skills start to become not all that interesting or fun to use, and decision-making fatigue definitely started to have its grip on my brain past the twenty-five-hour mark.

The thing is, Tales of Vesperia is really not that long. But it feels long. That can be a good thing, but it definitely isn’t in this game.

A lot of those issues stem from the pacing. The game is so afraid to give more control to the player and ends up throwing them in cutscene after cutscene after cutscene. Often during times where it’s really not even necessary for the plot.

At the risk of sounding extremely ignorant, let’s look at Dragon Quest XI as an example of a JRPG with good structure.

What the player spends time with in the game can be broken down into four parts: Exploration, Combat, Crafting and Story Cutscenes. Of course, there are other parts of the game, like party talk or gambling, but those aren’t mandatory and can’t really be curated.

Each component of it’s whole serves a different function for the player. Each component possesses a different sort of challenge and provides a different kind of engagement and ‘fun’ for players.

When looking at any moment of the game in chronological order, those components are mixed in different and interesting ways. Some sections are filled with exploration, with very little combat. Other sections are combat heavy, with cutscenes interspliced. There are breaks in between components where the player can relax and spend time crafting weapons and armor.

When components are mixed, it keeps things fresh in our brains. It can make a hundred-hour experience feel like twenty hours.

Tales of Vesperia has its story elements and cutscenes interwoven into its game so heavy handedly that it makes it’s forty-hour experience feel like one hundred hours.

The game cannot resist throwing a cutscene in your face at every moment. There are so many story beats that can’t be conveyed in any other way besides a cutscene that they’re interjected every three minutes (that’s a slight exaggeration).

What’s depressing is that it’s clearly a limitation of the game. Take any story heavy Triple-A game today. A lot of the story beats and exposition and character development happen while the player is playing the game. Those stories don’t have to halt all momentum just to let you know that one of the characters is very thirsty.

The things that Triple-A developers are able to do with modern games just isn’t possible with the budgets that JRPG developers got in 2008, or get now (aside from the teams behind Final Fantasy!)

Aside from storytelling limitations, Tales of Vesperia rarely gives us time to breath. There aren’t many moments of exploration (though the ones that are there are great). There aren’t very many areas where we can just look for items and hidden chests, with the occasional monster to spar with. Rarely are there areas off the beaten path worth going to.

But, despite those limitations, there are still genuinely interesting storytelling techniques.

Take the skits for instance. They’re essentially conversations that characters have outside of cutscenes that help with world and character building. Despite them being completely optional, I watched pretty much every single one I could.

What’s cool is that while most of them are triggered by just progressing the story, some of them are activated through other means. For example, having 100,000 gold saved up triggers a skit (but I’m not gonna spoil it!). A lot of them help flesh out the story, but they’re also really funny.

Also, the opening is HEAT.

Ultimately, the game has charm. The fixed camera perspectives, the pencil pushing spreadsheet-esque management, the chaotic combat. It’s charming.

Despite limitations (of which there are others, they’re just not entirely relevant), it’s actually fun to play. Which isn’t always the most important quality of a game, believe it or not. But it definitely matters with JRPGs.