Ori and the Will of the Wisps is very much a reboot – not a sequel – of Ori and the Blind Forest. It’s a revamp and improvement on every front. It feels different. Yet, it still possesses the original’s soul.

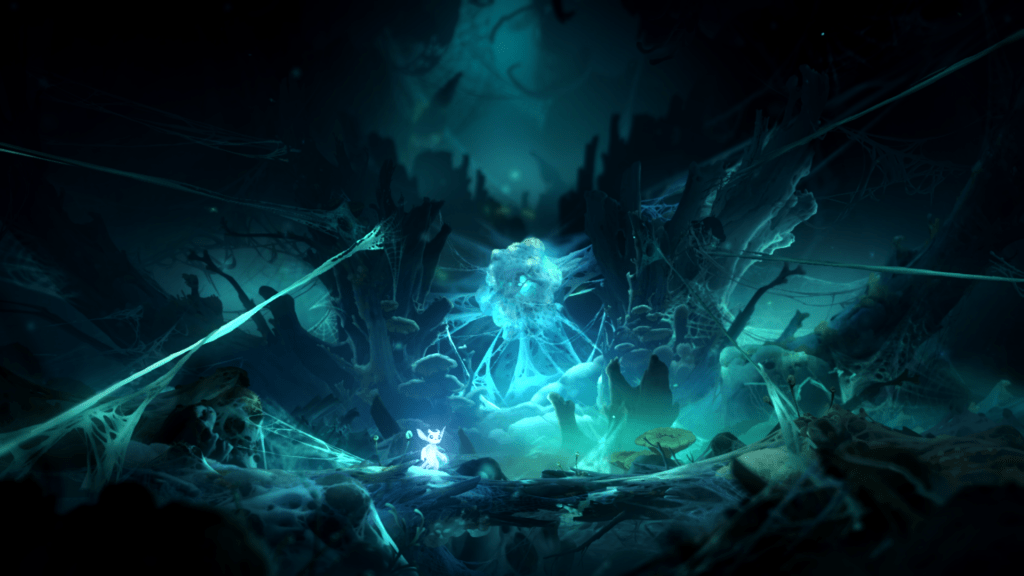

I’m dueling with a monster a hundred times my size. It lobs acid spit in my direction. I send them hurling back with my Bash ability. It slams its hulking claws down on top of me. With a fraction of a second to spare, I dash nimbly out of the way. It fires a sweeping laser-beam from up above, and a narrowly avoid it by scurrying up the cavern wall. That little maneuver sets me up face to face with the beast. And I slash it in the face.

In anger, it chases me from the boss arena. Targeting chandelier-like plants with Bash, rather than acid spit, sends me hurling, through a tunnel in the cavern ceiling. I use triple jumps and air dashes to clear deadly spikes that line the walls as the creature’s splayed jaws close in. With wall jumps, I scale the inside of a hollowed-out tree, jumping out into another cave just as it falls into the chasm below. The monster and I continue the struggle up above.

These moments are pretty much as close as your going to get to a perfect vertical slice for Ori and the Will of the Wisps. It has everything. And Moon Studios knew this, just look at the E3 2019 gameplay trailer.

For one, the presentation is phenomenal, just as it was with Ori and the Blind Forest.

The handiwork of the art team is pushed to the limit. The music swells and interjects Ori’s familiar theme during crucial turning points. It all just comes together as the sort of emotional climax of each story arc (since they pretty much always occur at the end of a huge section of the game).

If you want to make people froth at the mouth for your game at E3, show them these moments (if your game has them!).

It’s surprisingly ‘cinematic’ for a 2D game, as weird and borderline ignorant as that sounds, especially one that feels so retro in its design. Rather than borrowing from film to stage dramatic scripted moments, Ori does it in a way that’s more ‘video gamey’.

Moon Studios co-founder Gennadiy Korol said, during an interview at E3 2018, that the combat in Ori was slightly inspired by Dark Souls. Whereby to defeat enemies you end up engaging in a kind of dance with them.

Take one boss – which I won’t spoil – and how it requires you launch yourself out of the water to be able to hit it. Or how you need to avoid falling debris by going into the water, but need to get out when it spits its poisonous ‘ink’ at you, since it’s spreads more easily in water (I promise, it’s not an octopus).

While it’s puzzle like in its design, it’s more of a product of getting you to move than being a puzzle for the sake of it. The test doesn’t come from you figuring out what to do, it’s more of being able to pull off maneuvers during the right moments and taking advantage of that.

It becomes this weird lethal tango. And you’re dancing to music that gets progressively more intense as new phases begin (nothing new, but crucial). On top of that, the environments often change, in most cases getting more and more hazardous as fights continue.

While Ori is a game, you’re very much an actor playing a role during the more intense encounters of the game. We end up getting satisfaction from playing that role correctly too.

The more you dive underwater when you’re supposed to, and the more you launch yourself upward to hit that – not octopus – freak in the face, the more ‘rewarded’ we feel.

Because these moments are very much scripted set pieces. When we do it correctly, we understand how the experience was ‘meant’ to be had. The music feels more dramatic, and the environment hazards feel like actual dangers rather than scripted happenstances. When you die, some of that tension and wonder goes away.

It’s like that weird moment when you actually fail a QTE and you get a Game Over. Its immersion breaking! When you try it again, that desperate back and forth struggle against some guy trying to shove a knife in your neck as you mash the X Button isn’t really that scary anymore.

When my friend recommended Ori and the Blind Forest to me and told me not to fail the chase sequences because it would “ruin it!”, I was a little confused. But as I write this, I kind of understand where they were coming from. When you die over and over again during those moments (because I suck at the game), there’s definitely something lost.

But when you dance properly you get that full ‘cinematic’ experience. While The Last of Us might take inspiration from Children of Men, Ori and the Will of the Wisps takes inspiration from. . . Dark Souls?

Okay, so this vertical slice is great for trailers, sure. They’re also great cinematic moments – if you do them correctly. But they’re also good from just a ‘game design’ perspective.

One of the hallmarks of the Metroidvania genre is progressing by finding power ups scattered across the world. This progression is on two fronts.

The first of them is exploration. Let’s say at some point in a randomly made up game, you come across a wall that’s just a little too high to jump on top of. But you need to get up there to be able to move into a new area.

Well, you just store that place in your brain somewhere, and maybe you’ll figure it out later. During another moment, imagine you somehow get your hands on a jetpack that lets you shoot yourself up in the air for a second or two.

Hopefully, if you didn’t snort too much of that Elmer’s glue when you were a kid, and the designers have a certain attention to detail, you’ll immediately reach a wonderful epiphany. You can use the jetpack to reach the wall from before! This is you figuring it out later!

A tsunami of feel good juice floods our brain. We feel like we solved an elaborate puzzle or something! More importantly, we feel like we’re some kind of legendary adventurer.

This is a pillar that defines Metroidvanias. Getting us to feel like we’re discovering and interacting with the world for ourselves.

When looking at Ori and the Will of the Wisps, ‘Bash’ is a good example of this. During the game, you might notice these strange chandelier-like plants hanging from the forest canopy. They almost always on top of, or surrounded by, toxic pools and sharp spikes. And they almost always lead to some other area.

Because of those toxic pools and spikes, we can’t reach them. So, we leave them be. Later, we get Bash, which lets us use those lanterns to catapult ourselves in a direction of our choosing.

We immediately start thinking about all the places with those plants we saw from before (of which there are so many we can’t possibly remember them all, which can be either a good thing or a bad thing, depending on what you like). New locations become available to us.

I think where Ori takes this idea of ‘exploration progression’ a step further is in the movement. In the actual act of using your new abilities to explore new areas.

Bash feels incredibly good to use. Catapulting yourself at Mach 8 – okay, it’s not that fast – is an empowering moment. And that’s a key word: empowering.

As you get more and more abilities that allow you to explore the world, you start to move faster. At the beginning of the game, you’re a slow poke. You’re just some idiot. You can barely get two feet off the ground. Ori 1 was better at conveying this pathetic feeling, but Ori 2 does it well in its own way.

But then you get a dash. Now you can clear large gaps on the forest floor and move more quickly on the ground. Then you get a double jump, and can jump higher and farther. Then you get Grapple, which lets you latch onto specific surfaces from far distances. With Bash, you can catapult yourself at speeds you never thought you’d be moving at in this game.

Early Game Ori and End Game Ori are completely different things. You become a super hero at the end. Sections of the world where you once had to carefully maneuver one step at a time are zipped through in seconds. There’s this genuine sense of momentum.

This is no accident (if you think games can be designed by accident, which can actually be true sometimes. Not entire games, just game concepts. Did you know that the concept of the microwave oven was invented when Raytheon engineer Percy Spencer left his food under a military-grade magnetron?), trust me.

There are these poles placed in spicily dangerous areas that you can use to vault yourself off of – after spinning around a few seconds. Momentum isn’t something you can ‘sense’ in the game, it’s actually there.

You can use the momentum from your Grapple to not only reach those special surfaces, but launch yourself to new heights and distances. You can use multiple grapple points to swing around in those tantalizing Spider-Man swinging arcs from Spider-Man 2, or Insomniac’s Spider-Man (which I haven’t played yet, please don’t hate me).

The second front of Metroidvania progression is the combat. Going back to that randomly made up game, you might realize that your jetpack isn’t just good for scaling walls.

Let’s say there’s some freakish alien that has freakishly long spears for arms. But, imagine they were so heavy it couldn’t lift them more than a foot or two off the ground. It’s area of influence would extend well beyond itself, since it’s arm-spears are so long. Yet it’s unable to thrust upward at all.

If you’ve been having trouble with this type of alien in the past and you get your hands on a jetpack, you might reach another wonderful epiphany. You can pop up over the alien and bop it on its head!

Another tsunami of feel good chemicals washes over you. You feel like a master tactician. A legendary soldier. The Mother of Special Forces! (okay, I might be laying in on a little too thick here)

This is the other pillar of Metroidvania progression: getting us to feel like we’re discovering new ways to handle combat, for ourselves.

This sense of discovery might come from the fact that the abilities you use for combat are the same ones you use to explore. You immediately figure out that you can use your jetpack to scale some tall wall, but the thought of using that jetpack to kill aliens might come a little later.

If the game handed you a ray gun and said, “Here, use this to shoot aliens”, that would be one thing. That is technically a new way to handle combat. That’s ‘progression’. But it’s simply given to you. If you’re not discovering it for yourself – or at least given the illusion that you’re discovering that for yourself (which is what this really is at the end of the day, most of the time) – where’s the fun in that?

When it seems like you’re finding ways to approach combat on your own, that’s ‘real’ progression, and that’s powerful stuff.

In Ori, Bash is a good example of this. You can use it to catapult yourself from chandelier-like plants, yes. You can also use it, however, to catapult yourself from enemies.

Now, the game pretty much screams this in your ear when you first get Bash. It’s not entirely a secret that you can do this. Where the sense of discovery comes from though, is the zany shit you can do by catapulting yourself from enemies.

Level 0, being the most un-woke level, is using Bash to damage enemies (which is only possible in Ori 1, now that I think about it. You need an upgrade to do damage with Bash in Ori 2. This is even more fitting for the ‘most un-woke level’ since you’d need to let your preconceptions about Ori 2, after playing Ori 1, literally allow you to play the game wrong).

Level 1, is figuring out you can use Bash to get to get on top of enemies and pogo-stick them to death with your Spirit Sword à la Shovel Knight (or rather Zelda II: The Adventure of Link, sorry, I’m something of a cornball zoomer).

Level 2, being the point where we begin to open our third eye, is using Bash to catapult yourself to previously unreachable areas with enemies. This is most easily done with flying monsters.

Level 3, the final point that my meager intellect can fathom, is understanding that using Bash on an enemy sends them flying in the direction opposite to your trajectory. You can use this to send them hurling into the many spikes that line the games walls, killing them instantly. This is galaxy brain level stuff right here.

Each unique use of Bash is something that you can discover for yourself. While they’re not the most complicated things to figure out, there’s this sense that the way you tend to use these free-form abilities is an indication of how you like to play. It’s player expression, at its most elegant and simplistic. And that’s fun.

But, again, the abilities you use for exploration and the abilities you use for combat are the same. They serve both purposes.

There’s always been a deep link between the exploration side and combat side of progression in Metroidvanias. And I think Ori does a really good job of strengthening that link even further.

What you need to do to traverse dangerous environments and what you need to do to defeat dangerous enemies aren’t really all that different. They both involve a lot of movement. There’s a rhythm to the mechanics – a dance, if you will (I’m using the term ‘if you will’ ironically here, I’m not that edgy).

Reaching chandelier-like plants, Grapple swinging, Water Dashing, and everything else, require a certain rhythm. A particular kind of manipulation of momentum. You kinda just have to get a feeling for the undulations and the movement by playing the game.

Likewise, combat has a certain kind of rhythm. There are these stomping Praying Mantis type enemies (that are surprisingly reminiscent of Hollow Knight’s jumping bug type enemies) that require you to move side to side repeatedly – but not randomly – to avoid being smushed. There’s a pattern there. It slowly works its way inside your subconscious like an eldritch. . . ASMR. . . podcast?

Or take an even better example. Flying enemies often have you zipping around in mid-air yourself, trying to kill them. All of those mid-air motions are stuff that you also do while zipping through tunnels lined with spikes.

As you progress through the game and unlock more and more abilities, you become stronger on both fronts. You end up getting better at moving around, which becomes progress towards both exploration and combat. Not only in the literal sense of actually picking up new powers, but also learning to use them.

The more often you use these abilities, the more comfortable you become with them. Abilities like Bash become a multi-use tool at your disposal. You start to use them more often during the right situations. These abilities become your bread and butter. That’s growth.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in Ori and the Will of the Wisps’ sublime vertical slice segments. They often double as both boss fights and chase scenes. They see you using all the abilities you’ve learned for both high speed movement (trust me, both Ori 1 and Ori 2 will crush you if you don’t know how to go fast!) and high-octane combat sequences.

Not only are these moments a culmination at the end of a story arc. Not only are they emotional climaxes uplifted by the score and the art work. They’re also the culmination of everything we’ve learned about the game and a test of our skills. They’re not just emotional climaxes, they’re mechanical climaxes too. And that’s probably a part of why these moments stick in players memories so potently.

Despite that, I feel like there’s something missing with Ori. I think a lot of that comes from the fact that exploration wasn’t really that engaging for me.

Now, the actual act of traversing levels was fun. You could say that the structure of the game is very clean.

There are large sections of the game filled with quiet puzzle solving and light enemy interaction. During these moments, you spend a lot of time trying to figure out how to unlock a particular area of the level, which usually involves long treks around winding paths and experimentation with the game’s mechanics.

Other sections of the game are a bit more intense. Take the platforming for example. In the early game, it sees you carefully maneuvering tunnels lined with spikes and areas filled with toxic pools. End game sees you zipping past these areas at high speeds with triple jumps, air-dashes, grappling and everything else.

The game mixes these components well. It makes a short game feel longer as we come back to old areas with new tools in our ability pool. It keeps things fresh as we’re constantly challenged in new ways.

But the driving force, what makes me actually want to go out and explore the world, is largely missing.

What I’m referring to is this sense of wonder you feel when you reach a new and visually interesting area. Or the excitement of discovering a hidden path or a crack in the wall, as your brain does gymnastics trying to figure out where this new path might lead. Or this weirdly potent sense of sorrow a particular area might make feel, just through art and music direction.

These moments are almost intangible. But I think they come from world-building: making me believe this world you’ve created is an actual place.

Now, that’s kind of a tall order, especially for a ‘2D’ game. Getting people to believe a world that only operates in two dimensions sounds like something a crazy person would want to do – but only when you say it out loud. Games that look absolutely ridiculous have been immersing us for generations. It’s about suspension of disbelief. And some games walk that fine line really well.

Take a more modern example, and an example of a Metroidvania, Hollow Knight. Despite the elegant hand drawn art style of Ari Gibson (I say ‘despite’ because let’s face it, you’re not going to convince someone that 2D looks ‘realistic’ – no matter how wonderfully crafted the animation is – without having them already be accustomed to it by consuming animation, whether that be through anime or another medium. This is coming from someone that goes on sakugabooru. Have you ever tried to get a parent to watch anime? I have. That shit is not fun. I tried to get my dad to watch Akira a couple of years ago. Akira! He thought it was for ‘kids’. I guess in some respects, it kinda is.), the game still got me to believe in its world.

That’s because the game crafted a world that people – bugs – lived in. There are cities, there are mines. There are sewers, and roadways. The world follows logic that the player can follow.

If someone discovers a hidden path, they can speculate about where it might lead for themselves. There’s a certain kind of fun that comes with that. That’s only possible because that path operates within the space of the world. It’s not some loading zone to a completely random part of the world.

Then, when the designers wanna get really crazy and make, for example, a giant hole under the city à la Made in Abyss, it has a lot more impact. The moments where we find those horrors and those wonders are so potent because it stands in contrast with the world around it, and our belief in it.

Ori and the Will of the Wisps doesn’t really have any moments like that. The areas just feel like video game levels. And the thing is, that’s fine.

My issue is that there definitely was an attempt to create a ‘world’. You’ll often talk to NPCs that talk about the good old days when their race wasn’t extinct, or turned to zombies. You might run into a merchant that mentions how he’s traveled all over the land.

The areas in the game are supposed to be places. They have names and people used to live there. But Moon Studios never really goes all the way with these ideas.

Ultimately, that lead to a world that I never really felt any real calling to discover for myself. There was no spark, no moment where I was like, “Woah, what the hell is over here?!”.

Despite that, this game is still a wonderful achievement. Ori and the Will of the Wisps is very much a reboot of Ori and the Blind Forest. It’s a revamp and improvement on every front. The game feels very different. And yet, at the same time, it strangely feels like they’ve done it in a way that feels true to the original game. It still carries its soul. It’s characterized by moments of incredible speed, yet also moments of quiet exploration. There are still incredible ‘cinematic’ sequences that feel like they tie everything together.

I’ve seen a lot of people complaining about how a lot of the new design decisions in Ori feel like they were influenced by Hollow Knight, another extremely successful Metroidvania. The thing is, if those decisions are made in an effort to improve QOL, then I fail to see the issue.

All games take influence from those that came before it – often from areas outside of video games. Whether you like it or not, they all stand on the shoulders of giants.

Ori manages to do this and preserve its soul. Despite its many influences and predecessors, the game ends up doing its own thing – having its own flavor. And that’s really cool.

PS: Why is it called Ori and the Will of the Wisps and not Ori and the Will of Wisps? It just rolls of the tongue more. It’s also a play on words for the Willow tree (which is pretty important in the game!). Am I missing something here? Am I just stupid?